In addition to fiscal policies described in 3.8 — Fiscal Policy and 3.9 — Automatic Stabilizers, we also use monetary policies to influence the economy in the short-run. This allows us to develop further control over the aggregate demand curve, unemployment, and inflation. Similar to fiscal policy and automatic stabilizers, monetary policy helps manage fluctuations during recessions and inflation.

Typically, a combination of expansionary and contractionary fiscal and monetary policies are used to restore full employment when the economy is in recession or inflation output gaps. However, a combination of both fiscal and monetary policy works in the short-run but can have long-run effects, which is what we try to combat.

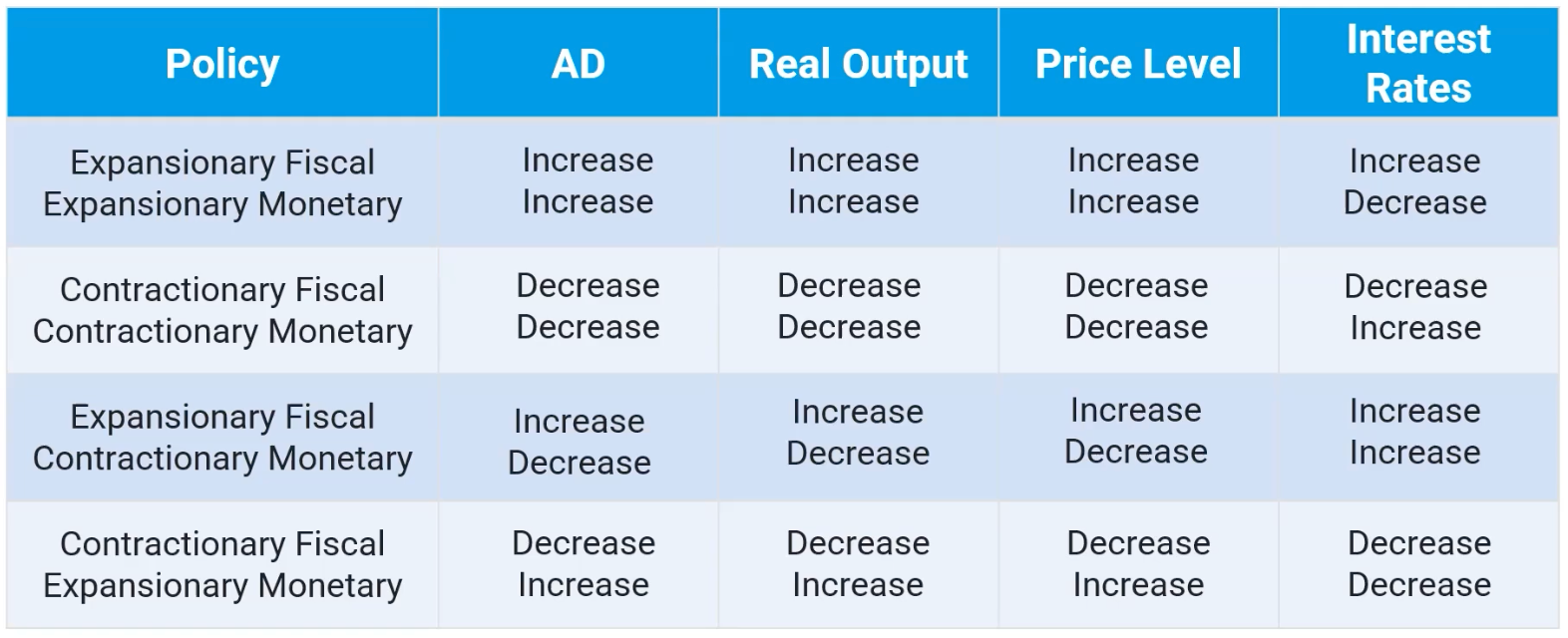

At the bar table, we see contradictions in the interest rate shifts. These are the kind of consequences we want to be aware of.

Fiscal Policy

In 3.8 — Fiscal Policy, we discussed discretionary fiscal policy and how governments utilize spending and taxation to assist the economy during fluctuations. The two main types of fiscal policy discussed were:

- Expansionary Fiscal Policy: which is used during recessions to help the economy operate back to its potential output. The government primarily increases its spending or reduces taxes, which directly and indirectly help boost consumer spending (and shift the AD curve right) respectively

- Contractionary Fiscal Policy: which is used when the economy is overheating to help combat inflation. The government primarily decreases spending or increases taxes, which directly and indirectly reduce consumer spending (and shift the AD curve left) respectively

However, fiscal policy has limitations. Its usually delayed due to legislative processes and excessive expansionary fiscal policy can lead to deficit and national debt. This weakness in fiscal policy is described as the Timing Problem. It has four essential parts:

- Recognition Lag: The time it takes to identify an economic problem (e.g., recession or inflation

- Decision Lag: The time required for policymakers to decide on the appropriate response.

- Implementation Lag: The time it takes to execute a policy once decided

- Monetary policy is generally quicker but still requires time to affect the economy

- Impact Lag: The time between policy implementation and its effects on the economy

Monetary Policy

Monetary policy is controller by the central bank (ex: Federal Reserve) and focuses on influencing money supply and interest rates to stabilize the economy. In contrast to fiscal policy, it indirectly shifts aggregate demand by altering borrowing and spending behaviours. The two main types of monetary policy are:

- Expansionary Monetary Policy: which is used to stimulate economic activity during recession. The central bank either increases money supply or lowers interest rates, which alters borrowing behaviour. This increases investment and consumer spending, which shifts the aggregate demand to the right. For example, a reduction in interest rates will increase mortgage and corresponding consumer spending

- Contractionary Monetary Policy: which is used to control inflation. The central bank reduces the money supply and raises interest rates, which alters borrowing behaviour. This decreases investment and consumer spending, which shifts the aggregate demand to the left. For example, high interest rates may decrease housing market activity and reduce consumer spending.

Monetary policy is faster than fiscal policy as it doesn’t require legislative approval.

Ratchet Effect

The Ratchet Effect refers to the phenomenon where prices, wages, or levels of government spending tend to rise during periods of economic growth or increased demand, but do not decrease proportionally during downturns or decreased demand. This creates a “ratchet-like” pattern where adjustments go upward but rarely move backward.

Essentially, during economic growth, increased consumer demand will raise production wages and prices, and governments may continue to increase sub-spending to support higher demand. Conversely, during economic downturn, the demand falls, and businesses and governments might not reduce prices and wages, which also leads to asymmetric adjustment