While long-run self-adjustment is an approach to helping the economy when it’s overheating or underperforming, fiscal policies are laws that are implemented by governments to stabilize the economy back to full employment. Tools of fiscal policy are mostly government spending and taxes.

Non-discretionary fiscal policy involves laws that automatically speed up or slow down the economy. They’re kind of like passive power-ups. These laws essentially increase government spending and decrease taxes when the economy is slow without introducing an entirely new law. Unemployment benefits and our bracketed tax system are an example of this. We’ll talk about non-discretionary fiscal policy in 3.9 — Automatic Stabilizers.

Conversely, this questioning fiscal policy involves new laws that are designed to fix the economy in a certain period of time. As mentioned earlier, these are just government spending and taxes.

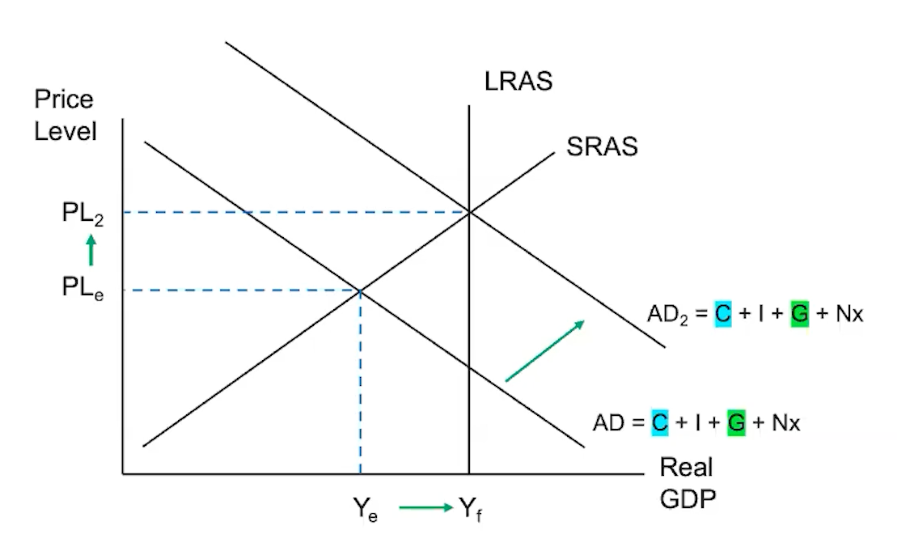

Expansionary Fiscal Policy

Expansionary fiscal policy is used when the economy is in a recessionary gap. In such an instance, government spending is increased (so AD shifts right) and taxes are cut (indirect impact on AD). Taxes don’t directly affect AD because it’s not a part of , , , and . However, they have an indirect effect because they affect consumer spending. Essentially, government spending has a large impact, while taxes have a smaller impact.

When an economy is in a recessionary gap, we have the following:

- Unemployment is growing

- Prices are falling

- Productivity is falling

When we use government intervention, like taxes and government spending, we shift the AD curve rightward, which results in an increase in employment but also an increase in inflation.

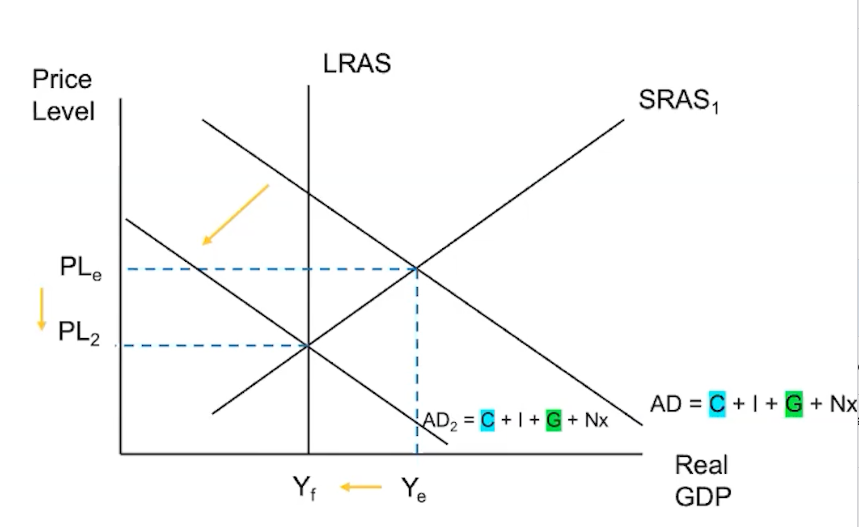

Contractionary Fiscal Policy

Contractionary fiscal policy is used in the reverse situation, which is when we have an inflationary gap. Government spending will decrease, shifting AD leftward. Taxes are increased, which will eventually shift AD leftward. Once again, government spending has a larger impact, while taxes have a smaller impact.

When an economy is in an inflationary gap, we have the following:

- Unemployment is low

- Prices are rising

- Productivity is rising too fast for firms to keep up

Once again, when we use government intervention, like taxes and government spending, we shift the AD curve leftward, which results in a decrease in inflation but also an increase in unemployment. Essentially, fiscal policy has its trade-offs.

If the government increases expenditures on goods and services while also increasing taxation by the same amount, we actually won’t have both offset each other. This is because government spending is a cause of the multiplier effect, which means government investment has a significantly higher impact on the economy than taxes itself. This stems from the idea explored in 3.1 — Aggregate Demand.

We know that the Marginal Propensity to Consume + the Marginal Propensity to Save is equal to 1. At the same time, we also know that the spending multiplier is equal to , and the tax multiplier is equal to . Ultimately, this always means that the spending multiplier is one more than the tax multiplier. For example, if the MPC is 0.4 and the MPS is 0.6, the spending multiplier would be and the tax multiplier would be . Therefore, in this hypothetical scenario, the spending multiplier is approximately one more than the tax multiplier.